Applying machine learning and AI to predict patient risk

To reduce adverse events at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Grenoble-Alpes (CHUGA) in France, Head of Public Health Prof Jean-Luc Bosson, MD (upper right), worked with Elsevier data science experts, led by Sigurd Prieur, PhD, VP of Life Science Analytics.

Healthcare, by definition, is supposed to make you better. But sometimes an infection is contracted at the hospital or a complication occurs after surgery. Such health-related adverse events occur in 8% to 12% of all hospitalizations, according to the World Health Organizationopens in new tab/window. There are 750,000 health-related adverse events in the European Union each year, which amounts to more than 3.2 million days of hospitalization that could have been prevented, WHO reports.

A 2017 report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)opens in new tab/window shows that more than 10% of hospital spending is related to the treatment of health-related adverse events that occur during hospitalizations.

The desire to improve this situation sparked a collaboration between Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Grenoble-Alpes (CHUGA)opens in new tab/window in France and Elsevier.

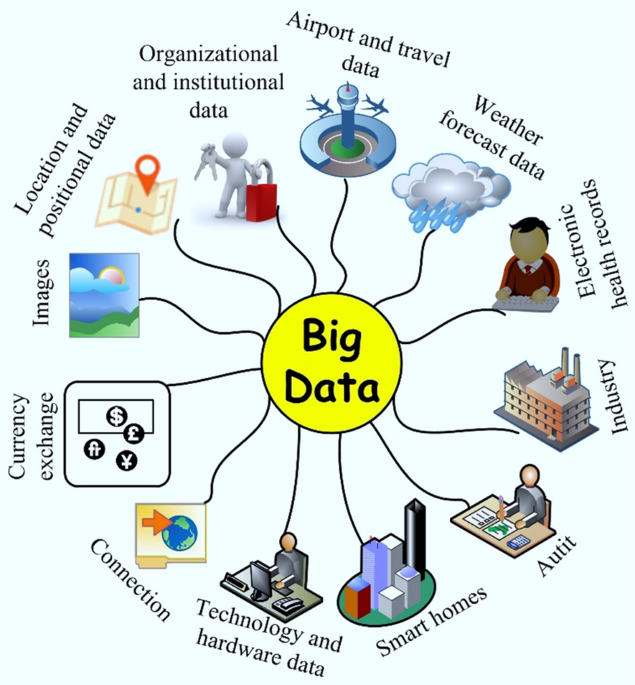

In 2019, Prof Jean-Luc Bossonopens in new tab/window, MD, head of the hospital’s Public Health Department, teamed up with Elsevier to apply machine learning to their historical patient data with the aim of creating models that identify patients at higher risk for healthcare-related adverse events. To do this, they needed to build a single multisource dataset, or “data warehouse,” that combined all the hospital’s internal data sources. This complex task involves sourcing data from different places, such as laboratories and radiology departments, and incorporating various types of sources, such as diagnoses, notes and orders from nurses and physicians. The task also requires resolving data mismatches and coding inconsistencies.

Over the course of the pandemic, the project team from CHUGA worked with Elsevier colleagues remotely to set up the pre-conditions for big data analysis using modern machine learning methods. Prof Bosson remarked:

This type of project benefits the patients first, but also the organization. Before, I viewed Elsevier essentially as a publisher of scientific journals. With this project, I discovered and understood Elsevier’s openness to a world we share — medical informatics and health analytics.

Prof Bosson’s ambition is now almost in place: simultaneous modeling of hundreds of variables to uncover relationships, look for patterns and define populations at risk. The models identify the top 5% of patients with a 4.7x increased risk for life threatening event lik thromboembolism or a 40% risk of a prolonged hospital stay. This will allow the hospital to flag patients that fit the risk profile and provide more directed care.

Without Elsevier’s data science teams, we would never have had the expertise and availability of sufficient staff to complete this project. Or we would have done it in five to six years, and the project would have been obsolete before it was finished. In this field, you have to have quick results because things move very fast.

link